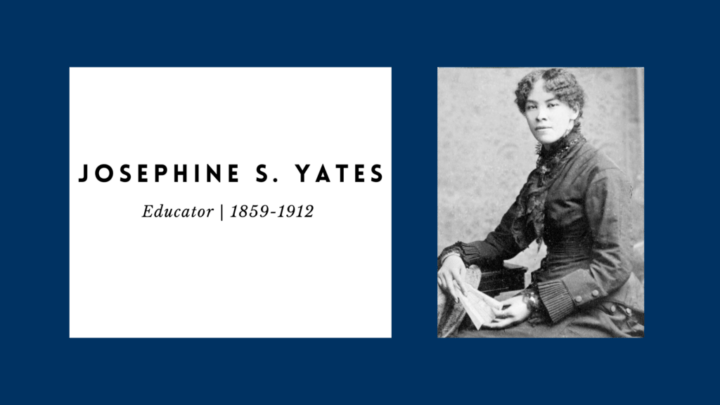

Josephine Silone Yates (1859-1912) was an educator, writer, and Black women’s club leader, whose career and community work was grounded in a commitment to “racial uplift,” emphasizing the improvement of newly freed Black communities post-emancipation. One of the first Black women professors in the United States, Yates taught at Lincoln Institute, now Lincoln University, in Jefferson City, Missouri (Dublin, 2020). Yates was integral to the establishment of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) in 1896 (Dublin, 2020), and as the organization’s second president (1901-1904), she put her knowledge to work by establishing the NACW’s infrastructure to expand early care and education opportunities for Black children across the country (Robbins, 2011).

Early learning and child development theory shaped Yates’s pedagogical philosophy and grounded her advocacy for day nurseries and kindergartens, which remains a less-recognized aspect of her life’s work (Robbins, 2011). Her writings evidence her pedagogical fluency through the discussion of various educational theories and research and distinguish her as a great thought leader in education across the human lifespan. Nonetheless, Yates’s intellectual leadership and expertise in education is woefully understudied, buried like the efforts of many 20th-century Black women whose perspectives on the role of education in Black liberation surpassed the boundaries of the Black men who dominate historical memory (Robbins, 2011).11. Writings by (and about) Black women thinkers and leaders like Nannie Helen Burroughs and Anna Julia Cooper, who helmed some of the first highly respected post-emancipation Black schools, reveal that they viewed their work beyond the confines of the industrial vs. liberal arts debate, most notably represented in W.E.B. DuBois and Booker T. Washington. From the nexus of Blackness, womanhood, and class, these women made contributions on how to respond to the systems of oppression facing Black people using intersectional and womanist concepts to shape the educational institutions needed to address post-emancipation Black life (Baker-Fletcher, 2007; Cooper, 1892; Johnson, 2009).

Early Life and Teaching Career

Josephine Silone was born in Mattituck, New York, in 1859 to Alexander and Parthenia Reeve Silone (Scruggs, 1893; Dublin, 2020). She spent her childhood living with relatives in different parts of New England in order to access better educational opportunities, a common practice among Black families that valued education for Black girls and made major sacrifices to facilitate their educational access prior to emancipation (Perkins, 1993)

At age 11, Yates moved to Philadelphia with an uncle to attend the Institute for Colored Youth (Dublin, 2020), a school founded by Francis “Fannie” Jackson Coppin, a highly respected educator and one of the first Black women to graduate from college (Perkins, 1993).22. Founded in 1837, the Institute for Colored Youth, which would later be renamed Cheyney Training School for Teachers (Jones, 1982) and finally Cheyney University, was the first Historically Black College and University. Coppin maintained an interest in Yates throughout her life and called her “a brilliant example of what a girl may do” (Scruggs, 1893, p. 42). After Yates’s uncle received a position as Chair of Theology at Howard University in Washington, D.C., Yates moved to Newport, Rhode Island, with an aunt (Dublin, 2020). Yates attended Rogers High School, where she was the only Black student (Scruggs, 1893; Dublin, 2020). She graduated as valedictorian of her class in 1877 and received the Norman Medal for Scholarship (Scruggs, 1893; Dublin, 2020).

Yates went on to graduate with honors from the Rhode Island State Normal School,33. Normal schools were teacher preparation programs offering a curriculum that ranged from two to three years in length and did not grant a bachelor’s degree but did not require a four-year secondary education for admission (Anderson, 1988). making her the first Black person eligible to teach in Newport public schools (Our Women Contributors, 1904). However, rather than teach locally, she moved to Missouri and joined the faculty at Lincoln Institute,44. At the close of the Civil War, the 62nd and 65th Colored Infantries wanted to create an educational institution for newly freed Black Americans, so they founded Lincoln Institute in Jefferson City, Missouri, in 1866. Although originally focused on teacher training, under the Morrill Act of 1890 the institution became a public land grant institution and expanded the curriculum to agricultural and industrial topics. This Historically Black College and University was renamed Lincoln University in 1921 (Lincoln University, n.d.). where she worked for eight years as a chemistry professor and the Chair of Natural Science (Dublin, 2020; Our Women Contributors, 1904). She left her position in 1889, when she married William W. Yates, a principal at Wendell Phillips High School in Kansas City, Missouri. The Yateses had a daughter who became a teacher and a son who became a physician (Dublin, 2020). In 1902, Yates returned to Lincoln as Chair of English and History, and by 1904, her biography states she “quite recently” received her master’s degree from National University of Illinois (Our Women Contributors, 1904).

Early Learning Theory as a Core Influence

Yates’s scholarly writings on pedagogy, child development, and education reform were boundary spanning.She explored the role of music in education (Yates, 1909a); the genealogy of the field of genetic psychology (Yates, 1905a); shifts in child development from interdisciplinary perspectives in psychology and child study (Yates, 1904b); and the benefits of a higher education curriculum that included both industrial education and liberal arts (Yates, 1895; Yates, 1907a; Yates 1909a).

A core influence on Yates’s pedagogical opinions was Friedrich Froebel, the German educator who invented kindergarten. In her writings, Yates holds Froebel in high regard, referring to him as “the education reformer” whose program based on nature established the “basis of a new education” (Yates, 1905a, p. 304) that “revolutionized educational thought” (Yates, 1904b, p. 250). Yates viewed Froebel’s kindergarten and concepts such as “self-activity” as deeply influential of the emerging industrial movement in education and applicable across the span of learning in primary, secondary, and higher education:55. In the late 19th century, the industrial education movement promoted technical, trade, and manual training (Anderson, 1988). The three strands of the industrial education movement included: 1) the highest-status programs in applied science and technology for supervisors of labor (trained engineers, architects, chemists, etc.); 2) trade schools designed to prepare for individual occupations; and 3) manual instruction to supplement the traditional academic curriculum to promote habits of industry (e.g., thrift, morality) (Anderson, 1998). White philanthropists advanced industrial education as a pedagogical and ideological approach that maintained Black subordination in the South by expanding educational opportunities designed to leave racial political and economic hierarchies undisturbed (Anderson, 1988; Dennis, 1998).

…and the great stress he placed upon self-activity foreshadowed the industrial movement in education which naturally followed in the wake of the kindergarten; and which served among other things, to prove that Froebel’s principles, in place of being limited in application to the earliest years, apply as well to each period or stage of life; and that each stage not only has a completeness of its own, but also that perfection in the later stages can only be attained by perfection in the earlier; hence the urgent necessity of well modeled courses in kindergarten and in primary instruction.

Josephine Yates (1907b, p. 288)

Early education theory was central in shaping how Yates thought about education and the significance of investment in early learning opportunities. She viewed human development as building upon each prior phase and saw kindergarten as “a movement destined to revolutionize educational thought from the lowest to the highest rounds of the same” (Yates, 1904b, 250). For Yates, Froebel’s kindergarten represented “far more than pastime for very young children; it involved principles applicable from kindergarten age and onward […] throughout life and the continuance of its activities” (Yates, 1904b, p. 250).

At the turn of the 20th century, different interpretations of Froebel’s theory and modifications in its application to kindergarten practice had begun to emerge in response to the influence of modern psychology and child study, as well as the expansion of kindergarten provision and its gradual inclusion in the public school system (Wheelock, 1908; Vandewalker, 1908). Yates spoke to this debate and argued that self-activity was a central principle of education (Yates, 1905b) and that play was a central part of “Froebel’s mastermind” (Yates, 1906, p. 294; Cunningham & Osborne, 1979). She believed his contribution “reveals to us the psychology of play in education, and the value of play as an educative force” (Yates, 1906, p. 294). She pushed back against drill and rote memory exercises, arguing that the purpose of education was to develop “thought power” — the ability to think for oneself long and hard with sustained, concentrated attention — that would lead to “thought expression, well directed initiative” (Yates, 1905b, para 44). The ends of education for Yates were to put one’s thought power to work and “engage in the world’s work” (Yates, 1905b, para 36), which she described as creation and change-making in the world, giving examples such as Michelangelo’s paintings, Shakespeare’s dramas, government administration, and the creation of the New York City subway (Yates, 1905b).

Although many White women educators likewise embraced Froebel’s approach to kindergarten, Yates interpreted his theories with an eye for how education should be designed to prepare Black children for a post-emancipation world (Robbins, 2011). For example, she argued that developing “thought power” was critical in addressing the challenges facing Black people and viewed Black teachers and education as a whole as important for improving Black life (Yates, 1905b). The context of segregated kindergartens and racialized expectations about appropriate educational approaches for Black children, often aimed at educating Black children for a racially and economically subordinated status, underscore the importance of Yates’s pedagogical contributions for the preparation of Black teachers and young learners.

In her study of Froebel and other pedagogical theorists, Yates made connections across the spectrum of human learning but also envisioned a more comprehensive approach to education. For example, rather than wholeheartedly committing to a singular theory of education, she asserted the necessity of “symmetrical development,” emphasizing an alternative pedagogical philosophy to the either/or debate of W.E.B. DuBois and Booker T. Washington that captures historical memory.66. Although the philosophies of W.E.B. DuBois and Booker T. Washington are too complex for in-depth discussion here, their opposing ideas about the type of education newly freed Black people needed linked a curricular focus to varying paths to freedom. While DuBois advanced liberal arts education as a path to radical subversion of the social order (including Black suffrage), Washington promoted industrial education as a path to Black economic independence, with vocational training often critiqued as an “accommodationist approach,” which left racial hierarchies undisturbed. Yates discussed the concept of symmetrical development in higher education and argued for both approaches. For example, she praised the work of the Lincoln Institute, writing that the president believed “most thoroughly in a happy combination of both higher and industrial education as a means of symmetrical development” (Yates, 1907a). In regard to the significance of a more comprehensive curriculum, Yates wrote:

We do not, indeed, need a smaller number of scholarly men and women, but a much larger quota of those who to their literary attainments add the power to produce something which is a necessity to the masses. We need not less intellectual training in the field of higher education, but more practical education.

Josephine Yates (1895, para 5).

Yates also applied this concept to teacher training. In an earlier piece outlining her opinions on the proper focus of teacher training, Yates (1904b) argued for the “symmetrical development of the physical, the mental, the moral, the spiritual qualities of personality” (Yates, 1904b, p. 248). Her pedagogical fluency translated into a robust approach to learning across the human spectrum, linking kindergarten to the aims of higher education for Black students and Black teacher training.

NACW Leadership: Day Nursery and Kindergarten Advocacy

Building on the foundation laid by Mary Church Terrell, the first president of the National Association for Colored Women, Yates’s presidency (1900-1904) continued to prioritize the establishment of kindergartens and day nurseries for Black children throughout the United States (Robbins, 2011). Her role as a national leader built on her earlier efforts as president of a local Black women’s club in Kansas City, where she led 150 members (Terrell, 1940). Viewing organizational work as the “first step in nation-making,” Yates took pride in the NACW as likely the largest and only “non-sectarian body of educated Negro women organized for the definite and avowed purpose of ‘race elevation’” (Yates, 1904a, p. 283).

Black club women were clear that their organizing was based on their distinctive view and experiences as Black women (Giddings, 1984; Jones, 1982; Roberts, 2004), rather than merely imitating White women’s efforts in their clubs or prioritizing Black men’s “political methods” (Yates, 1904a). Their work in early childhood was part of a range of broader activities, including anti-lynching, temperance, orphanages, adult education, and women’s business exchange efforts (Giddings, 1984; Roberts, 2004). However, in the histories of public kindergarten development, Black club women’s contributions to the field of early learning have not been discussed in great depth but are limited to a long list of activities and names (Allen, 2017; Beatty, 1995).

Black club women viewed kindergartens as a critical aspect of post-emancipation challenges facing Black communities (Robbins, 2011). The educational philosophy of kindergarten — training both mother and child — was seen as an opportunity to address what Black club women perceived to be one of the root causes of poverty and racial discrimination during this period: lack of education (Yates, 1905a; Robbins, 2011). Although this understanding placed the onus of change on Black children and mothers through assimilation and acculturation into White dominant culture, Black club women viewed the poor and working-class mothers they served as members of their broader community (Giddings, 1984; Roberts, 2004; Robbins, 2011). Roberts argues that “Black club women’s acceptance and facilitation of mothers’ paid labor differed starkly from white women reformers’ support of the ‘family wage,’ which assumed female dependence on a male breadwinner” (Roberts, 2004, p. 968). This difference emerged out of Black women’s lived experiences and the realities of Black women’s lives, which necessitated paid work and child care service, as well as public education.

The Black movement for day nurseries and kindergartens had the support of multiple institutions and organizations, including the NACW, the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), settlement houses, and Black churches (Cunningham & Osborn, 1979; Robbins, 2011). While HBCUs functioned as training sites and laboratories for early learning (Cunningham & Osborn, 1979), the NACW provided institutional infrastructure and financial resources for starting free or low-cost, private Black day nurseries and kindergartens and offered teacher training in places like Washington, D.C., while leading advocacy for the inclusion of kindergarten in the public school system.

At the end of her tenure as NACW national president, Yates wrote that the organization was moving away from the early “experimental” phase to an “aggressive campaign of growth’’ (Yates, 1904a, p. 286). Under her leadership, the NACW developed its organizational infrastructure and established a foundation of stability that supported that growth. When Yates spearheaded the NACW’s incorporation in 1904, she identified 14 areas of club work to which she appointed experienced leaders, including a kindergarten department to provide national guidance and support for kindergartens established by local Black women’s clubs (Robbins, 2011). Yates appointed Haydee B. Campbell, supervising principal of kindergartens for Black children in St. Louis, to lead this national kindergarten department. In a biography preceding her contribution to a special women’s issue of The Negro Voice in 1904, her administration was described as “marked by the great amount of valuable work accomplished in organizations, federation of states, also by the manner in which the work has been systematized, divided into departments and placed in the hands of capable superintendents, etc.” (Our Women Contributors, 1904, p. 262). By the time Yates completed her two terms as president, the NACW was 20,000 women strong (Robbins, 2011).77. Despite the emphasis placed on kindergarten by the first two leaders of the NACW, the focus of the organization shifted away from early education to temperance and women’s rights after the election of Lucy Thurman, Superintendent of the National Department of Colored Work with the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (Robbins, 2011). Though the WCTU was involved in establishing kindergartens and mother’s clubs as a way to support families impacted by alcoholism, the national NACW focus on kindergarten was never again as strong as under the leadership of Terrell and Yates (Robbins, 2011). Robbins (2011) noted that Thurman was the first non-educator elected as NACW president.

The National Association for Colored Women

“Lament if you will, the White organizations never could have set these women before us in the light which they have set themselves by their devotion to service and independent work. If colored women are lifted up it will be done only by colored women.”

Josephine Yates (1904a, p. 310)

The National Association of Colored Women (NACW) was established in 1896 by the merger of two Black women’s clubs: the National Federation of Afro-American Women and the Colored Women’s League (Jones, 1982; Brooks, 2018). The National Federation of Afro-American Women was organized by the Women’s Era Club, founded by Josephine Pierre Ruffin in 1895 with Margaret Washington as president (Jones, 1982). The Colored Women’s League was founded in 1892 by Black women in Washington, D.C. (Brooks, 2018) and described by Mary Church Terrell (1940) as the first Black women’s club organized with national intentions. The call for a national umbrella organization to unify club efforts throughout the United States was partly driven by a disparaging letter from James W. Jack, president of the Missouri Press Association, that attacked the morality of Black women (Terrell, 1940; Jones, 1982; Brooks, 2018). This letter was addressed in the June 1895 Women’s Era editorial with a call for unity among Black women’s organizations. Though the merger was challenging,88. Jones (1982) details the events leading up to the merger between the National Federation of Afro-American Women and the Colored Women’s League. The Women’s Era Club first organized the National Federation of Afro-American Women, and it took the lead in fusing with the Colored Women’s League. The Women’s Era Club publication, The Women’s Era, aroused local interest in a national convention, which was held in Boston in 1895. A letter from James W. Jack, president of the Missouri Press Association, on the morality of Black women was the catalyst for organizing nationally (Terrell, 1940; Jones, 1982; Brooks, 2018). At the convention, which included 100 delegates representing 20 clubs from 10 states, Josephine Pierre Ruffin called for a national umbrella organization. However, the Colored Women’s League was absent, so a committee of seven members from the group met to facilitate the union of both organizations on July 21, 1896, resulting in the NACW (Jones, 1982). the organizers realized they could achieve their goals “more quickly and more effectively if they were banded together throughout the country with heads and hearts fixed on the same high purpose and hands joined in united strength” (Terrell, 1940).

On Black Women as Educators

Being an educator was at the heart of Yates’s career. She felt that “the class-room was the place where her efforts would result in the greatest good to the greatest number” (Scruggs, 1893, p. 47). Yates applied and interpreted educational philosophy through the needs of Black mothers and children and asserted the importance of Black women as teachers and leaders in education. She believed that one of kindergarten’s strengths was that it brought together the training of mothers through Mother’s Clubs, children through kindergartens, and educators through teacher training (Yates, 1907b). Yates also argued that education was a key site where Black women’s efforts as teachers, directors, supervisors, and superintendents changed and “righted the direction” of the field (Yates, 1893). On Black women’s contributions in education, she wrote:

…from the kindergarten to the university, from the normal to the industrial school, as supervisors and as specialists, they have shown an aptitude for all-round honest work bounded only by the limitations of [t]ime and space. Often, out of slender salaries, they have laid the foundation of the school library, the kindergarten, or the industrial school. In fact, they seem to have considered no sacrifice of [t]ime or money too great which would in any way benefit the race.

Josephine Yates, (1893, para 5)

Yates clearly perceived Black women educators’ significant impact on the task of Black freedom. Black women were leading the work on the question of “the Negro Problem” in the schools, where it counted:

Within the last decade we have had a flood of talk (small and otherwise), of articles, and would-be legislation upon the so-called “Negro Problem” and its presumable solution; meanwhile our worthy teachers, many of whom are women, have patiently toiled on, in season and out of season, solving a knotty point here, correcting an error there, and really accomplishing more toward the final solution of the problem than all the articles, talk and legislation combined.

Josephine Yates (1893, para 6)

She pushed for teaching to be viewed as a profession that required a well-rounded program of training, study, and preparation, just as one would expect from a school of law, medicine, or any other professional school (Yates, 1904b). In her kindergarten expansion work with the NACW, she argued the critical importance of training kindergarten teachers: “The prime requisite of a well-equipped kindergarten is a well-trained teacher; and too much stress cannot be placed upon this part of the matter” (Yates, 1905a, p. 309).

One of Yates’s “happy results” for NACW kindergarten growth was in her home base of Kansas City, Missouri, where public education was offered to both Black and White children, but only White kindergartens had been established (Yates, 1905a, p. 308). After attending the 1899 NACW biennial meeting, the Kansas City Progressive Study Club successfully advocated the local school board for the creation of a Black kindergarten (Yates, 1905a). The club then contacted Haydee B. Campbell to request instructors for their newly established program. Two young women from the St. Louis Normal Kindergarten Training School began working in Kansas City’s Black kindergarten for the opening session in 1900 (Yates, 1905a). An article on St. Louis kindergartens reported that “we have sent two young ladies from this training class out to establish this work in Kansas City — Miss Lelia Warwick and Miss Ida Abbott,” who were Black women graduates trained by Campbell (Abbott-Sayre, 1902). An article reporting on Kansas City shows that Warwick and Abbott were well received, as “these kindergarten teachers were given the heartiest welcome ever accorded any newcomers to the teaching fraternity” (Grisham, 1902, p. 594). This successful transfer would not have happened without the leadership of Black women educators, particularly the connection between Campbell and Yates, whose local networks were undergirded by national leadership in the NACW.99. Warwick taught at Wendell Phillips High School, where Yates’s husband, William W. Yates, served as a principal (Grisham, 1902). Mr. Yates made necessary improvements to “make the schoolroom an attractive place for little ones” and reportedly asserted that “[i]f we are to have kindergarten we must have it right. I do not believe in half doing and makeshifts” (Grisham, 1902, p. 594).

On Black Women as Mothers

Yates believed in the power of Black women’s role within the home and drew connections between the domestic role of women to their role as teachers (Yates, 1893; Yates, 1907c). Although she acknowledged the advancement of women, noting that women’s sphere “is now conceded wherever she succeeds best” (Yates, 1905a, p. 305), Yates cautioned women not to abandon motherhood and the home. Like many Black club women who were her contemporaries, she believed in the power of Black women to effect change and racial uplift as mothers (Giddings, 1984,). Yates argued that slavery created conditions that limited the development of Black motherhood, while emancipation created a path to “bring out the best in womanhood” (Yates, 1907b, p. 289). She did not believe that schools and society could develop children in a “physical, mental, and moral aspect” in isolation and called on Black mothers and fathers to serve as good role models (Yates, 1907b, p. 289). Yates pushed back against gendered expectations that only women as mothers needed to live up to moral standards, arguing for a “single standard of morality” for men and women to set examples for their children as mothers and fathers (Yates, 1907b, p. 288).

For Yates, the unit of change was the home, and she argued that Black women’s clubs need to prioritize kindergartens and mothers’ clubs (Yates, 1905a). Calling for social change that linked the home, school, and society, Yates argued “these three act and react one upon the other in such way that whatever affects one affects the other; together, they are the triple forces which shape a race and make for its eternal weal or woe” (Yates, 1893, para 24). This philosophy guided the priorities of the NACW, which “has been through its branches in the various states a potent force in the formation and promotion of kindergartens, day nurseries, and mothers’ clubs” (Yates, 1905a, p. 307). These perspectives on the centrality of the home and motherhood, as well as Black women’s role in “race elevation” as educators, shaped commitments to expand both kindergartens and mothers’ clubs, which reached across the spheres of home and school.

Legacy in Early Education and Beyond

Yates’s legacy emphasizes the possibilities that flow from Black women’s organizing in early education and beyond: a multifaceted advocacy agenda that tackled child care and early education together and viewed these projects as a foundation of the commitment to racial and gender justice. Additionally, Yates brought a scholar’s mind to her advocacy and organizational leadership, which powerfully illuminates her contributions as a pedagogical thinker. By highlighting her life’s work, we make visible the lessons for 21st-century advocacy in the field of early care and education (ECE), as well as the importance of pedagogy rooted in a commitment to Black children and families.

The NACW’s advocacy for kindergartens and day nurseries made a groundbreaking contribution through the integrated understanding of the need for both care and education. When we fail to take seriously Black club women’s policy agendas and contributions to the public kindergarten movement, we rob ourselves of the lessons from the radical dimensions of their “distinctive angle of vision” (Collins, 2002), their commitments to racial and gender justice, and their lived experiences, which include the economic realities shaping Black families.

Imagine if our current system were built on the policy agenda of the NACW, with an integrated understanding of the necessity of early care and education as a public good. What a radically different starting place than the advocacy of White women’s care and education movements at the turn of the 20th century, which upheld gendered expectations of mothers at home with the youngest children, advocating for mother’s pensions rather than public child care investment at critical points in history (Michel, 1999). By shining a light on Yates as an educator, scholar, and leader, we make visible important lessons for today’s precarious ECE system.

Black Women, Labor, and Capital in the Early 20th Century

Implications of Black Women’s Advocacy for Day Nurseries and Kindergartens

[The Black woman] has been, and for some time must continue to be, at least “an assistant” bread-winner if the finances of the race are to be improved.

Josephine Yates (1904, p. 284)

“Further, that we shall have day nurseries for the infants and small children of laboring women who cannot remain in their homes and care for little ones, in order that these children may have proper nourishment and care, so necessary to the early years, that the atmosphere and environments about them may be pure and wholesome, and thus protect childhood and encourage any fond parents.”

(Washington, 1906, p. 85)

Although Black club women’s socioeconomic backgrounds positioned them differently from the poor and working-class Black mothers they served, their advocacy was simultaneously radical and conservative (Jones, 1982). To begin with, they attributed the challenges facing Black families to a broader social and economic context. NACW advocacy for day nurseries and kindergartens was influenced by the awareness that Black women were required to work due to the wage and employment exploitation of Black men, who could not meet heterosexual patriarchal expectations of a single male breadwinner household (Giddings, 1984; Jones, 1982; Roberts, 2004).

The radical work of Black club women departed from the pathologizing beliefs about Black families that guided the efforts of White women’s clubs, yet their conservative focus sometimes reinforced forms of gendered Victorian expectations, such as virtue (Jones, 1982; Roberts, 2004; Robbins, 2011). Their advocacy was rooted in the awareness of the economic necessity of Black women’s employment, but they also believed that the behavior of Black mothers and children would protect them from racial stereotypes and demonstrate deservingness of inclusion (Jones, 1982; Roberts, 2004). On the other hand, Black club women’s conceptualization of the issues facing Black people influenced how they approached and implemented kindergartens and day nurseries. For example, Mary Church Terrell used Mother’s Clubs to get a sense of labor issues and the impact of job loss in Black communities in order to support the NACW’s broader efforts addressing economic and social issues (Jones, 1982, Roberts, 2004). White women’s dominance in women’s advocacy cemented their specific needs or desires as the starting point from which to advance all care and education policy. Yet these needs and desires were disconnected from the realities of women of color and their families’ relationships with capital, labor, and education.

The split between care and education echoes today in the reliance on a market-based structure that limits accessibility to those who can afford to pay, while underfunding the wages for an ECE workforce of primarily Black and Latina women (Austin, et al., 2021). The current federal policy focus on universal pre-K for three- and four-year-olds risks keeping child care underfunded as a public good and at the whims of the market, while the ECE workforce is left without living wages and families are abandoned to high costs or a limited supply of publicly funded child care subsidies, despite the core function of child care to keep our economy running (Austin et al., 2021). The NACW’s legacy of integrated provision for care and education, which flowed from their profound understanding of Black women’s lived experiences, rings true for this particular moment in the ECE field.

References

Abbott-Sayre, H. (1902, May 24). St. Louis’ Kindergartens. The Colored American, X(7), 5

Anderson, J.D. (1988). The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935. University of North Carolina Press.

Austin, L.J.E., Whitebook, M., & Williams, A. (2021). Early Care and Education Is in Crisis: Biden Can Intervene. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/blog/ece-is-in-crisis-biden-can-intervene/.

Allen, A.T. (2017). The Transatlantic Kindergarten: Education and Women’s Movements in Germany and the United States. Oxford University Press.

Baker-Fletcher, K. (2007). A singing something: Womanist reflections on Anna Julia Cooper. In Waters, K. & Conaway, C.B. (Eds.), Black women’s Intellectual Tradition: Speaking Their Minds (pp. 269-286). University of Vermont Press.

Beatty, B. (1995). Preschool Education in America: The Culture of Young Children from the Colonial Era to the Present. Yale University.

Brooks, R. (2018). Looking to Foremothers for Strength: A Brief Biography of the Colored Woman’s League. Women’s Studies, 47(6), 609-616.

Collins, P.H. (2002). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge.

Cooper, A.J. (1892/1988). A Voice from the South. Oxford University Press.

Cunningham, C.E., & Osborn, D.K. (1979). A historical examination of blacks in early childhood education. Young Children, 34(3), 20-29.

Dennis, M. (1998). Schooling along the color line: Progressives and the education of blacks in the new south. Journal of Negro Education, 67(2),142-156.

Dublin, T. (2020). Biographical sketch of Josephine Silone Yates. Alexander Street. https://search.alexanderstreet.com. Giddings, P. (1984). When and where I enter: The impact of black women on race and sex in America. William Morrow.

Grisham, G.N. (1902). New features in schools of Kansas City. Southern Workman, XXXI(11), 591-597.

Jones, B.W. (1982). Mary Church Terrell and the National Association of Colored Women, 1896 to 1901. The Journal of Negro History, 67(1), 20-33.

Johnson, K. (2009). On Classical versus Vocational Training: The Educational Ideas of Anna Julia Cooper and Nannie Helen Burroughs. In Anderson, N. & Kharem, H. (Eds.), Education as Freedom: African American Educational Thought and Activism (pp 47-66). Lexington Books.

Lincoln University (n.d.). Our history. https://www.lincolnu.edu/web/about-lincoln/our-history.

Michel, S. (1999). Children’s Interests/Mothers’ Rights: The Shaping of America’s Child Care Policy. Yale University Press.

Our Women Contributors. (1904). Voice of the Negro, 1(7), 262.

Perkins, L.M. (1983). The impact of the “cult of true womanhood” on the education of Black women. Journal of Social Issues, 39(3), 17-28.

Perkins, L.M. (1993). The role of education in the development of Black feminist thought, 1860?1920. History of Education, 22(3), 365-275.

Robbins, J.M. (2011). “Black Club Women’s Purposes for Establishing Kindergartens in the Progressive Era, 1890-1910.” Dissertations. 99. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/99.

Roberts, D.E. (2004). Black club women and child welfare: Lessons for modern reform. Fla. St. UL Rev., 32, 957

Scruggs, L.A. (1893). Women of Distinction: Remarkable Works and Invincible Characters. L.A. Scruggs.

Terrell, M.C. (1940). The history of the club women’s movement. Aframerican, 1(2/3), 34-38.

Washington, M.M. (1906). Club work as a factor in the advancement of colored women. The Colored American, XI(2), 82-90.

Vandewalker, N.C. (1908). The Kindergarten in American Education. Macmillan.

Wheelock, L. (1907). Report for the committee of nineteen of the international kindergarten union. The Elementary School Teacher, 8(2), 79-87.

Yates, J.S. (1893). Afro-American women as educators. In Scruggs, L.A. (Ed.), Women of Distinction: Remarkable Works and Invincible Characters (pp. 309-319). L.A. Scruggs. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Women_of_Distinction/9IlNAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover.

Yates, J.S. (1895). Missouri. Woman’s Era, 2(3), 10-12.

Yates, J.S. (1904a). National Association of Colored Women. The Voice of the Negro, 1(7), 283-287, 310-311.

Yates, J.S. (1904b). The equipment of the teacher. The Voice of the Negro, 1(6), 248-252.

Yates, J.S. (1905a). Kindergartens and mothers’ clubs: As related to the work of the NACW. Colored American, VIII(6), 304-311.

Yates, J.S. (1905b). Thought power in education. The Voice of the Negro. 1(2), 242-248.

Yates, J.S. (1906). Education and genetic psychology. The Colored American Magazine, X(5), 293-297.

Yates, J.S. (1907a). Educational work at Lincoln Institute. The Colored American Magazine, XIII(2), 141-145.

Yates, J.S. (1907b). Parental obligation. The Colored American Magazine, XII(4), 285-290.

Yates, J.S. (1907c). Women as a factor in the solution of race problems. The Colored American Magazine, XII(2), 126-135.

Yates, J.S. (1909a). Industrial arts and crafts in America. The Colored American Magazine, XVIL(4), 237-238.

Yates, J.S. (1909b). Music as a factor in education. The Colored American Magazine, XV(3), 171-172.

Suggested Citation

Williams, R.E. (2022). Josephine Silone Yates: Pedagogical Giant and Organizational Leader in Early Education and Beyond. Profiles in Early Education Leadership, No. 3. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/publications/brief/josephine-s-yates-pedagogical-giant-and-organizational-leader-in-early-education-and-beyond/.

Acknowledgements

This paper was developed for the ECHOES project, which is generously supported through a grant from the Heising-Simons Foundation. Special thanks to Marcy Whitebook and Claudia Alvarenga for their collaboration and contribution to this project through thought partnership and archival research, and additionally to Claudia for graphic design.

Photo Credits

(1885). Josephine A. Silone Yates, educator and activist, seated before studio backdrop. (Photograph). Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016645948/.

Grisham, G.N. (1902). One of the first public kindergartens in Kansas City, Missouri. (Photograph) from New Features in the Schools of Kansas City. Southern Workman, XXXI(11), 595. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015018053093.